This post is dedicated to the late Catherine Marchand, who compiled the Blog Posthume and was interested in viruses and vaccines. She told me of the Spanish de Balmis expedition.

Summary

This story begins with the 18th-century French surveyor and scientist La Condamine, who participated in an expedition in Ecuador to determine the flattening of the Earth. In his footsteps, from Quito to Paramaribo, Hilbert vdM and I traveled in 2010, down the Amazon. Besides this return journey, I admire La Condamine for his advocacy of the then still risky smallpox inoculation, long before anyone knew what viruses were.

Next, I try to answer the question of what viruses actually are: genetic material (DNA or RNA) in a minuscule protein shell. They emerge from and multiply in all kinds of living cells.

How they were discovered (in 1898) and how they helped in the development of current molecular biology and vaccines, I try to illustrate using two timelines of discoveries.

Then the functioning of vaccines is briefly discussed, and finally the origin of the recent COVID-19 pandemic is addressed.

1. Introduction

Twenty years ago, on a trip with 2 rowing companions (H.vdM. and Ch.D.) to Suriname, we received a tourist poster by Paul Woei from our host couple, Dennis and Cindy Chin-a-Foeng (Fig. 1). On it we saw the name "La Condamine" for the first time. The caption read: "In 1744, La Condamine made a stop in Paramaribo after a long journey from the Andes down the Amazon river. Botanical specimens which he had lost on his way were replaced."

The adventures of the geographer and mathematician La Condamine were discussed in books by Hélène Minguet (1981), Florence Trystram (1987) and Neil Safier (2008; see References). Fascinated by these stories, two of us decided in 2010 to retrace the journey "in the footsteps of La Condamine." He was one of the 10 expedition members of a Franco-Spanish expedition that had to determine the shape of the Earth in connection with the controversy that had arisen between Newton (London) and Cassini (Paris) about the flattening of the Earth. For this, they had to accurately measure the distance over the Earth's surface between two points on a line (meridian) between Quito and Cuenca (about 3 degrees of latitude) with the length standard of the time, the toise. At the same time, the start and end positions of the line at Quito and Cuenca were determined based on astronomical measurements. Because with flattening at the poles, the arc distance over 3 degrees of latitude is greater at the pole than at the equator, they could establish that the Earth is flattened at the poles, as predicted by Newton.

Fig. 1. The sculptor Paul Woei (1938-2024) with his poster in Paramaribo, 2005; see: https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Woei.

My admiration for La Condamine was first aroused by his courage to descend the largely unknown Amazon river on the return journey to Paris, with all his notes, measuring equipment and collected specimens (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. After having made measurements between Quito and Cuenca (Ecuador) for 9 years, Charles-Marie de la Condamine undertook the return journey to Europe in 1743, together with his friend Pedro Vicente de Maldonado. See: Blog "La Condamine's voyage" (2007).

A second reason concerns La Condamine's scientific approach. Unlike his two colleagues, the mathematicians Godin and Bouguer, La Condamine wanted all three of them to make their measurements and calculations public. The others refused this, which led to distrust, quarrels and uncertainty about the results.

A third reason to mention La Condamine here is his involvement, together with other expedition members, in the serious outbreaks of the smallpox virus in Quito and Lima. Two of the expedition members were doctors and actively involved in immunizations through "variolation" (infecting healthy people by introducing pus from the pustules or pocks of sick people into a small cut in the skin). On his return journey and also later in France, La Condamine was an advocate of this method. Later, as a well-known person in Paris, he had himself inoculated to demonstrate the harmlessness of the "vaccine." Where did he get the courage or insight and confidence in a time when people had no idea of the "disease germs" (cells, bacteria, viruses) that caused so many people to die from this terrible disease?

Now we know that smallpox is caused by a virus, a structure that we can isolate and against which we can make vaccines. But first we must try to understand what viruses actually are.

2. What are viruses?

All living organisms are made up of cells (see Appendix A1, "Rooms and cells"). In Fig. 3, three different types of cells are depicted on the same scale: (1) a cancer cell (called HeLa), which here represents all "higher" animal and plant cells that have a nucleus in which the DNA is packed; (2) a primitive, single-celled yeast cell (baker's yeast), also with a nucleus; (3) a single-celled bacterial cell (the intestinal bacterium Escherichia coli), which has no nucleus, but a nucleoid.

All these cells can produce viruses, much smaller structures as indicated in Fig. 3. A virus is a very small "package" with genetic information (called genome) consisting of DNA or RNA, surrounded by a protective protein coat. Viruses are therefore not cells, but are built with the same molecules (including proteins) as those of the cells from which they originated.

Viruses have no cytoplasm, the blue-colored "contents" of the 3 cells shown in Fig. 3. Cytoplasm is a gel-like fluid with a high concentration of proteins (mainly enzymes; see Fig. 4). In this cytoplasm, the many biochemical reactions take place that ultimately make possible the production of energy and the synthesis of macromolecular "building blocks" for DNA, RNA and proteins. Thanks in part to this cytoplasm, cells can grow and divide. The cytoplasm is surrounded by a cell membrane (black line). Membranes also surround the so-called organelles that are also in the cytoplasm as round or elongated vesicles. Examples of these are the mitochondria, which produce energy, the endoplasmic reticulum, where proteins and viruses are made, or the vacuole in yeast (see Fig. 3). Bacteria have no organelles.

Without cytoplasm, viruses cannot produce energy and therefore cannot grow and divide like cells. However, they can penetrate cells of the same type as those from which they were formed, and "take over" the synthesis reactions of the cell, allowing them to multiply in the cell, using the energy produced by the cell.

Fig. 3. Scale comparison of a cancer cell, a yeast cell and a bacterial cell. The cytoplasm is colored blue. DNA is colored red. All "higher" cells have a nucleus and are therefore also called "eukaryotes." The gray area in the nucleus is the nucleolus. It contains the genes for the production of ribosomes (see Appendix A3). The straight, black lines in the cytoplasm are microtubules, also called spindle fibers, with which the chromosomes are transported to the future daughter cells during cell division (mitosis) (see Appendix A3). Bacteria have no nucleus, but a so-called nucleoid and are therefore called "prokaryotes." The double arrows indicate that a virus formed by a certain type of cell can also infect that cell again. As an example of a virus, the Corona virus is shown on a different scale. The diameter of this virus is about 300 nanometers (nm).

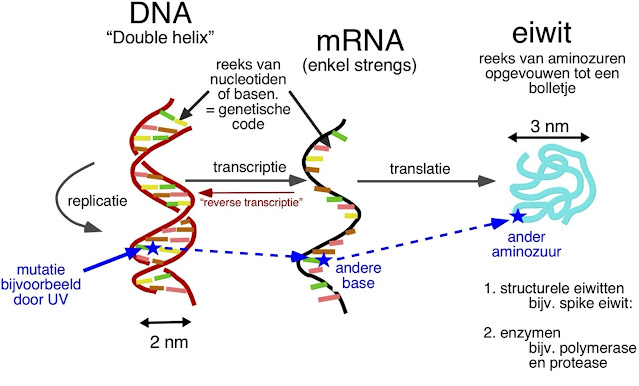

In every living cell there is DNA, which can duplicate itself (in the so-called replication process). This DNA is "transcribed" to mRNA ("messenger-RNA"; the so-called transcription process). Subsequently, the mRNA is "translated" into proteins (in the so-called translation process). In Fig. 4, this "central dogma of molecular biology" from 1958 is shown (see also Blog "Dogma, virus and vaccine", 2020). At that time, people were convinced that the hereditary information, recorded in the sequence of the nucleotides (also called bases) of the DNA, "flows" as it were from DNA to RNA and then from RNA to protein. Both these processes, transcription and translation (see Fig. A2 in Appendix "Rooms and cells"), would be irreversible. This means that no RNA can be made from a protein and no DNA from RNA. But as early as 1970, Temin and Baltimore (see Coffin and Fan, 2016), independently of each other, found an enzyme that could make a DNA single strand from an mRNA strand, the so-called "reverse transcriptase" (see Fig. 4). Retroviruses such as HIV and corona viruses make use of this enzyme (see Appendix A3).

The structure of cells is largely formed by so-called structural proteins. So-called functional, non-structural proteins (enzymes) take care of the many biochemical reactions in the cell, such as replication, transcription, translation, transport, regulation and energy production. Examples of structural proteins are the tubulins, which form the spindle fibers, and the spike protein of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (see Fig. 3).

If, due to DNA mutation in the cell nucleus (e.g., by ultraviolet radiation or by errors in the replication process), a base (the colored blocks in Fig. 4) changes, a change can occur in the genetic code, in which the hereditary properties of the cell are recorded. This can result, via the changed mRNA, in a different amino acid being incorporated into a protein during the translation process. Subsequently, this can cause the structure and function of this protein to change. If the protein gets a new function through one or more mutations, one speaks of "gain-of-function." These mutations can be detected by determining the sequence of the bases (nucleotides) in DNA or RNA; the sequence determinations are called "sequencing" and are comparable to the PCR test (polymerase chain reaction), with which genetic abnormalities, diseases and viruses can be characterized. It is such mutations and the change in protein structure that determine the changing properties of viruses such as SARS-CoV-2.

In 1898, the Delft microbiologist Beijerinck (Fig. 5) demonstrated that a disease-causing tobacco plant extract could not be a bacterium because after passing through filters that stop all bacteria, it could still infect other plants. He called (as the first!) the disease-causing fluid "virus" (the Latin word for "poison"). With this, tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) became the first virus to be described in detail. In 1958, a model of it was presented at the World Exhibition in Brussels (Fig. 5, right), made by Rosalind Franklin. She was also involved in the elucidation in 1953 of the structure of DNA, of the so-called double helix as drawn in Fig. 4.

Fig. 5. In 1898, Beijerinck confirmed the filterability of tobacco mosaic virus, TMV. The pathogen was therefore not a bacterium, but a "fluid" that could multiply in cells. He called it "virus." Right: In 1958, Rosalind Franklin made a model of the virus consisting of a hollow protein tube (diameter 18 nm), in which a single-strand ssRNA molecule is packed. This model later proved to be correct.

In 1917, Félix d'Hérelle of the Institut Pasteur in Paris discovered an invisible structure that could kill bacteria. It was a parasite on bacteria or rather a bacteria-eater that was called bacteriophage. Because bacteria can grow and divide and produce energy, just like "higher" cells, viruses have also emerged from such cells.

During my biology studies, I learned to culture and isolate bacteriophages in 1964. In 1966, they could be photographed at the Electron Microscopy Laboratory (Fig. 6). The peculiarity of these viruses is that they inject their DNA (linear double-stranded DNA) into the bacteria using a hollow tail. This is in contrast to most viruses of higher, eukaryotic cells, which usually take up the structures in their entirety by endo- or phagocytosis.

Especially in Russia, bacteriophages are still used as (alternative) therapy against antibiotic-resistant bacteria (such as some

E. coli bacteria).

Fig. 6. Electron microscopic images of bacteriophage T2r taken in 1966 by Nanne N. Cf. Fig. 1b in Woldringh, 2023. (A) Two bacteriophages made visible by shading with platinum. The icosahedral head (capsule) is clearly visible. Instrumental magnification 30,000x. (B) Bacteriophage “stained” with uranyl acetate. Attached to the DNA-containing head is a hollow tail ending in a base plate containing protein fibers that allow the bacteriophage to adhere to the bacteria. Instrumental magnification 360,000x. The diameter of the phage head is ~80 nm. (C) E. coli bacteria with many adsorbed bacteriophages. Instrumental magnification ~25,000x.

3. Timelines of Scientific Discoveries and of Virus Infections and Vaccinations

The timeline in Fig. 7a of biological discoveries begins with the observation by Robert Hooke (London) in 1665, that cork tissue consists of compartments, which he called "cells." A few years later, in 1674, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (Delft) described that he saw in a drop of water with his microscope "incredibly many small animals," often in the form of rods. He made the first drawings of bacteria (bacterium is the Greek word for rod, which was not introduced until 1838). Only two centuries after their discovery, in 1877, are bacteria recognized by scientists such as Robert Koch (Göttingen) and Louis Pasteur (Paris) as pathogens.

As described in Fig. 5 and 7a, the first viruses are discovered and described at the beginning of the 20th century. With the unraveling of the structure of DNA as a double helix and of antibodies as large, composite proteins in the 1950s, molecular biology begins around 1964 with the discovery of special proteins that can "cut" DNA molecules, so-called restriction enzymes. Such enzymes were used to make the first genetically modified intestinal bacterium, Escherichia coli (see Boyer and Cohen, 1972). This marked the beginning of the so-called recombinant DNA technology.

In February 1975, a conference was held in Asilomar (California), with lawyers, doctors and journalists in the audience. People were afraid that the genetically modified intestinal bacteria would endanger researchers and the public. At this unique and public conference, strict rules were discussed that researchers had to follow. Thanks to these restrictions, the public gained more confidence in science and research could continue.

Now, 50 years later, recombinant DNA technology, together with the containment rules, has become routine in medical and biological laboratories. No cases are known where a large public has ever been endangered. Nevertheless, fear of the rapid progress of recombinant DNA techniques and distrust in the construction of genetically modified organisms arose again among the public. How can it be explained to a layperson that genetically modified food cannot cause cancer? This requires a long and intensive period of knowledge transfer.

The timeline of infections and vaccinations (Fig. 7b) begins in ancient Egypt (3000 BC), where evidence has been found in mummies for the presence of both smallpox and polio.

The smallpox virus caused a pandemic in Europe in the 18th century, where it caused ~400,000 deaths per year. In the 17th century, the disease had already been brought to the New World by the Spanish. Around 1620, 80% of the Indian population in the Amazon region had died from smallpox. Even during the expedition of Francisco de Orellana in 1540, the accompanying monk Carvajal described how flourishing, densely populated Indian villages were located on the banks of the Amazon. Because La Condamine found nothing of this 200 years later, his descriptions were considered exaggerated (See: Orellana, 1540).

The collapse of the empire of the Aztecs (1520) and that of the Incas (1530) during Spanish colonization is not only attributed by historians to the possession of swords, horses and firearms, but especially to the deadly smallpox disease.

.jpg)

The timeline of infections and vaccinations (Fig. 7b) shows the progress of slowly acquired insights into the disease process of especially smallpox (variola, la petite vérole). Also indicated are the epidemics of influenza, polio and finally COVID-19 (caused by the corona virus, SARS-CoV-2). The observations of the disease process of smallpox in so many sick and dying people had already led around 1500 in China to the application of the above-mentioned technique of "variolation." Via India and the Ottoman Empire, this treatment method came to Europe in the 18th century, where a smallpox pandemic was then raging. In 1798, in England, among others, the physician Edward Jenner discovered that he could make people immune by infecting them with pus from the blisters of people suffering from cowpox (Vaccinia virus). This caused only a mild illness in humans. He was the first to use the name "vaccination" for this (from vacca or cow in Latin.) At that time, the first anti-vaccination movement also arose during Jenner's experiments.

.jpg)

In Spain in 1803, the "Balmis expedition" was equipped to spread cowpox "vaccines" in the New World. On board the ship equipped for this purpose were 22 orphan children who were successively infected with pus from the smallpox blisters of a sick child, in order to keep the "vaccine" alive and preserve it.

It is now difficult to imagine that these developments and treatments were applied without any knowledge of the existence of bacteria (first observed by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek in 1674, but only described by Pasteur as pathogens in 1877), or of viruses (only described in 1898; Fig. 4), let alone of molecules such as DNA, RNA or proteins, such as antibodies (see Fig. 7a). Research into these macromolecules only really got going after World War II.

In the United States, a major polio epidemic broke out for the first time in 1952: 57,000 people died and 21,000 became paralyzed. Thanks in part to a successful campaign called "March of the Dimes," started by President Roosevelt (he had contracted polio in 1921), a large-scale vaccination experiment was begun there. From the blood serum of polio patients, Jonas Salk developed a vaccine of inactivated virus.

Thanks to similar vaccines against smallpox, it could be declared in 1980 that the Variola virus had been eradicated worldwide. The poliomyelitis virus has only been declared (virtually) eradicated since 2020.

Finally, both timelines (Fig. 7a and b) indicate that we are now dealing with the coronavirus from Wuhan, SARS-CoV-2. This caused the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019. Worldwide, there were more than 700 million confirmed cases of COVID -19 and 7 million documented deaths on April 13, 2024 (Worldometer, 2024).

Immediately after the outbreak, a controversy arose among scientists about whether the new virus came from a "natural reservoir" of bats or other animals (zoonotic origin) or had been accidentally released from one of the eight laboratories in Wuhan ("lab-leak" theory). Both possibilities are discussed below.

4. What Happens During Vaccination?

When viruses enter our body and our cells during an infection (e.g., via the nasal mucosa; Fig. 8), we can become ill from this. At the same time, our body recognizes the viruses as foreign proteins (antigens), against which our immune system, which is present everywhere in our body, reacts with a defense reaction, the immune response.

This means first of all that white blood cells or lymphocytes (so-called helper T-cells) are activated by the spike antigen to secrete cytokines (or interferons) as signal molecules (Fig. 8). These cytokines then activate other white blood cells (T- and B-cells), which produce antibodies (IgG; IgM) against the spike protein. These large proteins, discovered in 1959 (see Fig. 7a), inactivate the virus, so that it can no longer penetrate cells using the spike proteins and cannot multiply. Moreover, they mark the virus so that it can be engulfed and broken down by killer T-cells.

This is called the first immune response, in which antibodies are made for several days; during this time you can become quite ill.

Antibodies are slowly broken down in our body (in 12 to 52 days after infection). However, our immune cells remain as dormant cells ("memory B-cells"), which can remember the virus. They are reactivated upon a new infection or vaccination (the so-called booster shot), whereby they change into plasma cells, which make antibodies faster and in larger quantities (second immune response). After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, it quickly became clear in 2020 that vaccines should also be developed against (part of) the spike protein.

Both infection and vaccination cause an immune response, but in different ways. First, you can become ill from infection, hardly from vaccination. Through infection, thousands of new viruses can be made in the infected cells, which infect new cells in your body again (see Fig. 8).

Secondly, in the process of virus production in infected cells, the proteins encoded by the virus (~33 in SARS-CoV-2) are also made. Some of these are strong immune response inhibitors. Other proteins cause red blood cells to stick together or break down, causing fatigue (as possibly in long- COVID disease). Such effects cannot occur with vaccination, because only mRNA is introduced that codes for part of the spike protein, the so-called receptor-binding domain. None of the other ~33 virus proteins therefore enter your body.

5. Uncertainty About the Origin of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus

According to statements made by Robbert Dijkgraaf, the newly appointed professor at the University of Amsterdam, the gap between science and society seems to be widening, including when it comes to viruses and vaccines (Dijkgraaf, 2025). This is despite the fact that thanks to research and education we are learning more and more about viruses and vaccines, and never before have so many students been working in medical and biological laboratories.

This gap is also fueled by distrust of the corona policy conducted by the government. This distrust is reinforced by, among other things, the aversion to so-called "Big Food" and "Big Pharma" institutions. That aversion led in the US, among other things, to the appointment of Robert F. Kennedy as the current Secretary of Health and Human Services. He is the hope of many Americans for a change in unhealthy eating and drinking habits and for a reduction in additives in food by supplement manufacturers. His opinion on unfounded health claims, including that vaccines can cause autism, are accepted in the bargain.

From the beginning of the corona period, distrust of science and anger at the government in the Netherlands was reinforced by TV programs such as Black Box by Flavio Pasquino (2020) and organizations such as "Artsen Collectief - 2023" (formerly called the anthroposophical "Artsen COVID Collectief"). In a publication by the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, the various groups that reject vaccinations are discussed (see reference Rijksinstituut, 2021). In these groups, the healing power of nature and thus of your own defense system (immune response) is emphasized with great certainty.

What is not mentioned, however, is that viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 can make various proteins that counteract the immune system in the body by breaking down important signal molecules (such as interferons). Therefore, during corona infection, good physical condition may sometimes be insufficient. Nevertheless, vaccine refusers continue to trust that their own immune response is sufficient to resist diseases such as COVID -19.

This trust in your own immune response of the human body reminds me of the pseudo-scientific movement in the 1990s: this claimed that many biological systems and structures such as the human retina or the bacterial flagellum, but also our immune response, cannot be explained by Darwin's theory of evolution and must therefore have been brought about by an "Intelligent Designer" (see Behe, 1996; Intelligent design movement). It is good to realize here how, for example, our hereditary properties are stored in our DNA: only 1 to 2% of the DNA in our chromosomes is used for coding the approximately 21,000 different proteins that function in our body. The rest of our DNA consists of ~50% non-functional "remnants," including transposable DNA elements (so-called "jumping genes") and DNA from no longer functioning retroviruses. It seems that the "Intelligent Designer" made a mess of it! That was also the assumption of the French microbiologist François Jacob (1982), who described the evolution of the human genome as "tinkering" ("bricolage" in French). Jacob nevertheless concludes that, despite this "tinkering," the formation of a human being capable of playing piano and crossing a busy street is the most bewildering problem and amazing story on our planet!

Back to the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Rozanne Hertzberger gives an exciting argument about the search for the origin of this coronavirus in an article in Elseviers Weekblad (2023). She is very critical of the dangerous gain-of-function research, which is also carried out in the Netherlands (by among others R.A.M. Fouchier of the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam). Lack of understanding of and transparency in this type of research has further fueled distrust in this type of research.

Regarding the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, scientists mention 2 possibilities:

(1) The lab-leak theory, where one of the many studied SARS viruses would have escaped or been deliberately released from the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV). China's refusal to provide access to laboratory data fuels suspicion of covering up a possible laboratory accident, where researchers became infected. Due to lack of laboratory data, this theory is difficult to verify further.

(2) The natural origin theory, where the virus has broken through the species barrier between animal and human through mutations (see Fig. 4) (this is called zoonotic spread).

What speaks against this second theory is that no animal hosts with precursors of the virus have been found. As early as January 2020, samples of animals and humans were taken at the Huanan food market (wet market) in Wuhan. Research of these samples (Mallapaty, 2024) showed that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was not present, but that the immune system of some animals (including the Raccoon dog) had been activated in a reaction to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Nevertheless, no smoking gun therefore, to speak with Rosanne Hertzberger (2023), but it did uncover a disturbing, illegal trade in poorly cared for live animals that can infect each other but also humans.

So although the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has thus far not been established with certainty for either theory, research on the natural-origin theory has expanded rapidly. Microbiologist Alexander Crits-Christoph and his colleagues found evidence of the virus in barns containing animals, including raccoon dogs and civet cats. Some samples even had genetic material from animals and SARS-CoV-2 together on one swab (Crits-Christoph, 2024).

In connection with the prevention of future epidemics, it is important to know the origin of SARS-CoV-2. From a medical standpoint, it is important to improve information about viruses and vaccines so that more people have enough confidence to get vaccinated. However, we must note that despite the increased knowledge about viruses and vaccines, the emotions against them have remained the same since the time of Edward Jenner's "vaccine" (1798; Fig. 7a). What is striking about the resistance to current vaccines is the certainty with which the dangers of vaccination and genetic research are described in conversations and on websites. André Gide (1869-1951) already warned against this certainty in his book "The Counterfeiters" (Les Faux-monnayeurs, 1927): "Croyez ceux qui cherchent la vérité, doutez de ceux qui la trouvent - Believe those who seek the truth, doubt those who have found it."

6. References and LINKS

Artsencollectief (2023): https://artsencollectief.nl/immuniteit/

Black Box (2020): https://www.blckbx.tv/

"blckbx is an independent, critical and integer news platform for free thinkers with a strong sense of justice. The blckbx, established during corona, makes programs from its own studio in which, among other things, conspiracy theories are discussed. Opinion pollster Maurice de Hond, activist Willem Engel and politicians such as Wybren van Haga and Thierry Baudet are regular guests. The broadcasts typically attract tens of thousands of viewers."

Behe, Michael (1996). Darwin's Black Box: The Biochemical Challenge to Evolution (1996).

Blog "La Condamine's voyage" (2007):

http://www.conradlacondamine.com/2007/03/voorbereiding-reis-bogot-leticia-manaus.html

Blog "Dogma, virus and vaccine" (2020): https://woldringh-naarden.blogspot.com/2020/12/dogma-virus-en-vaccin.html).

Boyer & Cohen (1972): https://www.sciencehistory.org/education/scientific-biographies/herbert-w-boyer-and-stanley-n-cohen/

Coffin, J.M. and Fan, H. (2016) "The discovery of reverse transcriptase". Annual review of virology, vol. 3: 29-51:

https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-035556

Condamine, Charles-Marie de La, (1981). Voyage sur L'Amazone - Choix de textes, Introduction et notes de Hélène Minguet. Librairie François Maspero, Paris. ISBN 2-7071-1219-4.

Crits-Christoph, A., .....and F. Débarre (2024) Genetic tracing of market wildlife and viruses at the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cell 187: 5468-5482.

Dijkgraaf, Robbert (2025):

https://www.uva.nl/content/nieuws/persberichten/2025/04/robbert-dijkgraaf-benoemd-tot-universiteitshoogleraar-aan-de-uva.html?cb).

Hertzberger, R. (3 April 2023). Elseviers Weekblad:

https://www.ewmagazine.nl/kennis/achtergrond/2023/04/rosanne-hertzberger-waarom-het-aannemelijk-is-dat-het-coronavirus-uit-een-lab-afkomstig-is-1035458/.

Jacob, F. (1982) "The possible and the actual" (Evolutionary tinkering). Pantheon Books, New York. ISBN 0-394-70671-4.

Kennedy, Robert F.: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cze391y17z7o

Mallapaty, S. Ill animals point to covid pandemic origin in Wuhan market. Nature 636: 284-285 (2024).

National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (2021): www.rijksvaccinatieprogramma.nl

Orellana, Francisco de (1540): https://qcurtius.com/2019/11/03/francisco-de-orellanas-epic-navigation-of-the-amazon/

Pasquino, F. (2020). Stichting Blckbx. https://www.blckbx.tv/over-blckbx

Safier, N. (2008). Measuring the New World. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago and London.

Trystram, Florence. (1979). Le procès des étoiles. Éditions Seghers, Paris. ISBN 2-232-10176-2.

Woldringh, C.L. The Bacterial Nucleoid: From Electron Microscopy to Polymer Physics - A Personal Recollection. Life 2023, 13, 895.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ life13040895

Worldometer, 2024: Infections and deaths from Coronavirus.

https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#google_vignette

Appendix A1. "Rooms and Cells"

All living organisms are built from cells. The comparison of rooms in a building with biological cells of an organism reveals striking similarities as well as fundamental differences.

An important building block for houses are bricks. An important building block for cells are proteins. The dry weight of cells consists of 40-60% proteins. While bricks are virtually all identical, proteins are, on the other hand, very different in shape, size and function.

Fig. A1. A house (building) is built from rooms, just as a body is built from cells. In a house, many different rooms and spaces can occur, such as hall, toilet, staircase or corridor. A body also has many different cells, depending on the genes that are expressed in the nucleus in the transcription process (Fig. 4). Depending on the types of proteins that are made in the translation process, cells acquire different functions, such as blood cells, muscle cells or brain cells.

To build a house with rooms, a bricklayer uses bricks together with building materials such as cement, sand and gravel. The cells of an organism all have the same type of wall, called a membrane. Through a process of self-assembly, proteins together with fatty acids can form the membranes that surround cells and organelles.

Just as bricks are formed from sand and gravel, proteins are built from amino acids.

Besides their construction, there are two other important differences between rooms in a house and cells of an organism: (1) a house has at most one room where the construction instructions are stored. In an organism, each cell contains a nucleus with chromosomes, in which the DNA is packed with the genetic information for the construction of the cell. (2) a house can only be enlarged by adding rooms to it. An organism can, surrounded by water, grow larger because the cells grow and after division give two daughter cells.

Fig. A2. The translation process in which ribosomes make proteins. In the HeLa cell, transcription of DNA takes place in the nucleus (red); in the cytoplasm (blue), there are ribosomes (diameter 20 nm), which "translate" the base sequence of the mRNA into a sequence of amino acids. The amino acid chain folds into a protein (diameter ~3 nm). Each ribosome makes one individual protein.

Appendix A3. "Origin of Viruses"

Viruses may have originated from errors made in the processes of replication and transcription, where pieces of DNA or RNA are packaged through a process of protein assembly. It seems as if this has happened at all different macromolecular synthesis processes at some point through deregulation in possibly primitive cells. Viruses are in any case classified into 7 classes depending on the genetic information (the so-called genome) that is packed in the virus (see the red arrows in Fig. A3).

Fig. A3. Different forms of nucleic acids (DNA or RNA; double-strand or single-strand) can be packaged into a virus through spontaneous self-assembly of proteins. Single-strand (ss)DNA arises during the process of DNA replication; double-strand (ds-)RNA through replication of ssRNA.

Classification of viruses into 7 classes:

1. dsDNA (double-strand DNA)

Variola virus (smallpox; la petite vérole) (linear DNA; 200 genes; ~300 nm diam. Multiplies in bone marrow, spleen and lymph nodes).

Vaccinia virus (Cowpox) (linear DNA; 250 genes; ~300 nm diam. People who become ill from cowpox are subsequently protected against the Variola or smallpox virus).

Varicella zoster virus (chickenpox; mainly in children; shingles or Herpes zoster in the elderly) (linear DNA; 70 genes; ~200 nm diameter; the virus hides, multiplies and moves in spinal nerves; the immune system therefore does not clear this virus; the Shingrix vaccine is therefore recommended.).

Polyoma virus (small virus with a circular genome of 5000 base pairs and 40 nm diameter. An example is the SV40 virus, which in the 1950s was suspected of causing cancer. This was seized upon by anti-vaccination activists. Later it turned out that there are no indications for this, although the virus can cause disease.)

T-bacteriophage. (The DNA is injected into the cell; see Fig. 6).

2. ssDNA (single-strand DNA)

3. dsRNA (double-strand RNA)

4. (+)ssRNA (positive, single-strand RNA = mRNA) (From this RNA, DNA is first made ("retro-transcription"), which then replicates in the nucleus just like a dsDNA virus.

SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Corona Virus-2, causes the disease COVID-19, which stands for "Coronavirus Disease 2019". The 11 genes of the virus code for 33 proteins, including 16 non-structural proteins (nsp1-16); ~100 nm diam.).

Rubella virus (causes German measles).

Poliovirus (Small virus with 7500 base pairs and 30 nm diameter. Can enter the central nervous system and cause meningitis or paralysis (poliomyelitis)).

Norovirus: a group of viruses that are important causes of diarrhea. It is estimated that worldwide 50% of all gastroenteritis is caused by these viruses.

TMV (Tobacco mosaic virus)

5. (-)ssRNA (negative, single-strand RNA)

From this, positive RNA is first made, which is then translated by ribosomes into viral proteins (see translation process; Fig. 4).

Influenza virus. (8 RNA segments code for 17 proteins).

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

Ebolavirus (filament-shaped; 7 proteins);

Morbillivirus (measles; 8 proteins; virus infects epithelial cells of, for example, the skin).

Paramyxovirus (causes mumps).

6. (+)ssRNA (single-strand RNA; retrovirus). Retroviruses contain a positive-strand RNA molecule that is transcribed into DNA. Subsequently, it is replicated as a dsDNA virus in the cell nucleus.

HIV (1983).

7. dsRNA (double-strand RNA)

Hepatitis B virus.

Appendix A4. Glossary

amino acid: Building block of proteins; a chain of amino acids forms a protein (Fig. 4). A cell makes 20 different amino acids.

antibody: Protein produced by the immune system that binds to viruses or bacteria to neutralize them.

antigen: Foreign protein or molecule that triggers an immune response in the body. For example, the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

bacterium: Single-celled micro-organism without nucleus; sometimes causes infections. Often rod-shaped.

bacteriophage: A virus that infects and destroys bacteria ("eats" them).

chromosome: structure in which the long DNA molecule (the double helix) is wound around clusters (so-called nucleosomes) of different proteins, the histones. This allows the DNA to be packaged into "manageable" bodies.

cytoplasm: fluid in the cell where biochemical processes take place and in which the organelles are located (Fig. 3).

DNA: Carrier of genetic information in cells. Consists of nucleotides (also called bases).

endoplasmic reticulum: Network of membranes in the cell involved in the production and transport of proteins, fats and also viruses.

endocytosis: Process by which a cell takes up substances or particles (viruses) by engulfing them with its membrane.

enzyme: Protein that accelerates chemical reactions without being consumed (compare catalyst).

protein: the most important macromolecule from which cells are built (see Fig. A2). There are many types of proteins, different in size, shape and function. Each protein is formed by a chain of amino acids that are linked together by ribosomes in the so-called translation process. The sequence of amino acids is determined by the genetic code of the mRNA (see Fig. 4).

"gain-of-function": Genetic modification that gives an organism or virus a new or improved function. Here viruses are modified to investigate their infectivity and virulence (ability to multiply). One wonders whether this type of research is carried out with sufficient security.

gene: Segment of DNA that codes for a specific protein. The sequence of nucleotides determines, after translation, the sequence of amino acids in the protein. Three nucleotides form a so-called codon that is specific for coding one of the 20 amino acids.

genome: The complete set of genetic information (DNA or RNA) of a cell or virus.

immune system: The body's defense system against pathogens such as viruses and bacteria.

infection: The invasion and multiplication of micro-organisms or viruses in the body.

interferon: Small proteins (also called cytokines) that are made by white blood cells (lymphocytes) and occur naturally in our body. They function as signaling molecules that trigger the immune response (see Fig. 8).

lymphocyte: Type of white blood cell involved in the body's immune response.

microtubules or spindle fibers. Built from the structural protein tubulin (see mitosis).

mitochondrion: Organelle that produces energy by burning nutrients; the 'powerhouse' of the cell. This organelle still contains DNA as a result of symbiosis with a bacterium.

mitosis or nuclear division. The process in which the duplicated DNA in the form of compact chromosomes is transported using microtubules to the future daughter cells; after this, cell division can take place.

mRNA (messenger RNA): Molecule that transfers genetic information from DNA to ribosomes for protein production.

mutation: A change in DNA that can affect the characteristics of an organism.

nucleolus: Nuclear body, an area in the nucleus where ribosomes are made (Fig. 3).

nucleotide: Building block of DNA and RNA, consisting of a base, sugar and phosphate group. There are 4 different base molecules.

organelle: Membrane-bound vesicle in the cytoplasm of "higher" cells. They have a specific function, such as energy production in mitochondria or protein synthesis or virus production in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mitochondria contain DNA because they arose from bacteria (symbiont theory).

protein: Macromolecule formed from amino acids, essential for cell structure and function.

ribosomes: A ribosome consists of 2 complexes (subunits) of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and a large number of ribosomal proteins. The 2 subunits are made in the nucleolus (Fig. 3). In the cytoplasm they bind to the mRNA in the process of translation.

receptor: Part of a protein on the cell surface that detects and binds signals or molecules such as viruses.

replication: The process by which DNA is duplicated to enable cell division or virus multiplication.

reverse transcription: See Fig. 4: In this process, a DNA single strand is made from an RNA strand by the enzyme reverse transcriptase. It occurs in so-called retro-viruses and also in the corona virus SARS-CoV-2; see Appendix A3.

restriction enzyme: Enzyme that can cut DNA at specific places; important in genetic research for making genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

spike protein: Protein on the surface of coronaviruses that helps them enter cells by binding to the ACE2 receptor.

transcription: The copying of DNA to mRNA as the first step in protein synthesis. Takes place in the cell nucleus.

translation: The process of translating mRNA into a sequence of amino acids by ribosomes in the second step of protein synthesis. Takes place in the cytoplasm.

Naarden, June 14, 2025

With thanks for the conversations with friends and family members who did not want to be vaccinated and for comments and suggestions from Kristof B., Matthias B., Misja vdH., Jelle vO.; Norbert V.; Ad T.; George B.; Bob W.; Jan and Loukie K.; Vic N. and Lidie W., for corrections by Mek V.

and for additional information by Diego M., Danny R. and Rob S.

C.L. Woldringh

Eng.jpg)

%202.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-Kamers&CellenEnglish.jpg)

.transcriptie-Engels.jpg)

.DNA-(+;-)RNA-eiwit.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)