The

cannonade of Candi-Karanganyar

Nederlandse

samenvatting volgt hieronder.

On

19 October 2017, it was 70 years ago that the "Cannonade of Candi-Karanganyar"

took place. The first time I read about it was when I found the website of Ravie Ananda in a search for "Keboemen" in September 2015.

On

this website Ravie Ananda describes the history of the Mexolie-factory where both our fathers had worked in the

1930's and the 1970's. He also writes

about the history of the war in Keboemen and about the cannonade on Candi-Karanganyar,

that took place on October 19, 1947.

The website of

Ravie Ananda, in which he describes the cannonade on 19 October 1947.

It appeared that the dutch journalist Max van der Werff (NCRV-TV) and

the indonesian historian Ady Setyawan had visited Ravie Ananda already in 2013

and had reported about this cannonade, in which 786 people were killed, on the

dutch television. I could not find any additional information about this

incident. Also, in the thesis of Rémy Limpach, which I obtained in January

2016, the cannonade on Karanganyar was not mentioned (Post #29- okt. 2016). Helped

by Dr. Bart Luttikhuis (KITLV), I started to retrieve information about the

cannonade from the Dutch National Archive: it appeared that most details of

Ravie Ananda's description were confirmed by dutch battle reports (Post #30, 17

December 2016 and Post #31, 2017).

After making a call in the veteran magazine "Checkpoint", I

was contacted by Map de Lange, a veteran of the second "Police

Action" of 1948. Together with Rémy Limpach and Azarja Harmanny, we

watched at the NIMH the documentary "Tabee Toean"(1995) by Thom

Verheul (see Post #31, 11 May 2017). The movie shows four dutch veterans visiting

their locations of combat actions on Java. One of them, the artillerist Henry

Pezy (3-6RVA), tells how they fired from a road at Gombong about 3000 granades with

12 cannons. "I am still curious about what has become of the people in

Karanganyar", he remarks when visiting the market of Candi.

Visit to the

veteran Map de Lange, who has an impressive documentation about the Dutch

colonial war (May 1, 2017).

After studying the battle reports and other documents obtained from

the National Archive, Map de Lange makes the observation that the Army

Commander Spoor only became aware of the cannonade 10 days later. The question

who ordered the bombardment will perhaps be answered by historians involved in

the newly started research project on the decolonization war. However, as argued

below, this study has a more important purpose!

"Vergangenheitsbewältigung"

(public debate on a problematic period)

In his article ("Geschiedenis Magazine", nr. 4, June 2017),

Rémy Limpach is wondering how

countries like France, England and Germany have coped with their colonial past.

His examples include the French in Algeria (-1962) and the English in Kenya

(Mau-mau, 1952-1960). The Germans seem to have successfully overcome the

Holocaust and helped by the Allied Occupation Forces, they received the image

of "Weltmeister der

Vergangenheitsbewältigung". But unfortunately, their dealing with the

1904-genocide committed in Namibia is still under way.

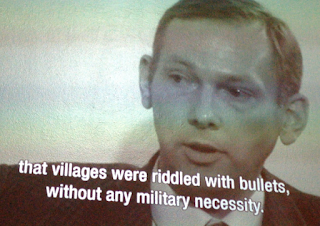

Benjamin

Ferencz: "If people are made into beasts" and "Governements must

stand trial to explain their behavior for a judge". During his visit (19 May

2017) to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in the Hague.

But what about the Dutch in the period 1945-1950? Almost everything is

known and documented. But the lost war has so far been hushed-up efficiently.

The crimes described are shocking. But can they surprise us? According to

Benjamin Ferencz, Neurenberg's former prosecutor, the war makes murderers of

decent people. In an interview he talks about the brutes of the so-called "Einzatsgruppen"

who killed about one million people behind the front in Eastern Europe:

Although each of those men have hundreds of deaths on their

conscience, Ferencz does not believe that they were bad by nature. "It's a big mistake to think so. I

wondered how a man like Otto Ohlendorf (Commander of one of the

Einzatsgruppen), highly educated and

father of five children, could have been able to do that. My conclusion is that

war makes killers of otherwise decent people. These men were patriots who

believed they served the interests of their country. "

Limpach notes that the negotiations between the Netherlands and the

Indonesian Republic in the period 1945-1950 were in fact a farce. How was that

possible? Did the government officials in the Netherlands and in the colony not

have the least incentive to reach a political solution? Did these government

officials just go for war?

The dutch journalist John Jansen van Galen does not agree with the

above: according to him the dutch governement pursued a Union between Indonesia

and the Netherlands on a voluntary and equal basis and never wanted to conserve

its colony...... It seems to me that the historians should be able to describe

the facts here. If Limpach's description is right the debt claim lies not only

in the Dutch armed forces but also in its leadership, the public administrations,

both in the colony and in the Hague.

Decolonization,

violence and war in Indonesia, 1945-1950

On September 14, 2017 the kick-off for the program

"Decolonization, violence and war in Indonesia" took place in

Amsterdam. The three institutes, KITLV, NIOD and NIMH, will receive a financial

support of 4 million euros for this research.

From the

"stream" of the kick-off meeting on 14 September 2017: A sometimes

uncomfortable conversation between Wouter Veraart, Rémy Limpach, Esther Captain

and Marjolein van Pagee.

Critical questions were asked by Annelot Hoek and especially by Marjolein

van Pagee (1). It seemed as if Marjolein van Pagee missed something in the

framing of the research proposals. Was it the involvement or identification

with the opponent, one of the most uncomfortable things to achieve? She pointed

out that we are going to Indonesia, but we are not listening to the

Indonesians. "Talk with them", she exclaimed

Azarja Harmanny went to Kebumen (August 2017) to talk with Ravie Ananda. Here they are

standing in front of the monument at Candi.

There is something behind the anger of Marjolein van Pagee. Is it the

same anger as felt, for instance, by Afro-Suriname people in the Netherlands,

when the government expressed her sincere regret about slavery and slave trade

in the past? Such recognition is worthless if not supported by the white community.

I think that Marjolein van Pagee tries to make us aware that this

study about decolonization, violence and war in Indonesia should not only be

about its historical facts. It should also tell the Dutch community about the

Indonesian people who had suffered, although standing on the winning side. We

know so much about the life of Dutch people in the colony, almost on a daily

basis like in the case of my parents (e.g. see french Blog Posthume). But what do we know

about the (grand)parents of, for instance, Ravie Ananda, who suffered not only

the war, but had been living in an "apartheid" society, as emphasized

by Prof. Wouter Veraart in the panel discussion during the kick-off meeting of

September 14?

This study of the 1945-1950-war in Indonesia should give us additional

facts but also help us to identify with the Indonesians. Only when a larger

part of the Dutch community recognizes and accepts the historical injustices

committed there, the governement will be able to perform a "policy of

regret" (2). Only then will this investigation of the decolonization have proven

its necessity and value.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

(1) Marjolein van Pagee,

is freelance researcher and journalist. She founded Histori Bersama in

September 2016. The activity of the foundation is to translate recent

publications from Dutch and Indonesian media that refer to the colonial past

and the Indonesian decolonization war (1945-1949).

(2) Ewout Tenhagen; scriptie onder

begeleiding van dr. Remco Raben,

Universiteit Utrecht; "Duiding van een donker verleden", 10 juli

2017:

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Nederlandse samenvatting

In dit blog, geschreven 70 jaar na de "Cannonade op Candi",

beschrijf ik hoe dit onderwerp is ontstaan. Daarna ga ik in op een artikel van

Rémy Limpach, waarin hij voor diverse landen nagaat hoe zij hun dekolonisatie

verwerkt hebben. Ik verwijs daarbij naar het bezoek (in mei 2017) van

oud-Neurenberg-aanklager Benjamin Ferencz aan het Internationaal Strafhof (ICC)

in Den Haag, Hij pleit ervoor dat uiteindelijk ook een regering voor begane

wandaden terecht moet staan.

Tijdens de kick-off op 14 september jl. van het door de regering

gesubsidieerde onderzoek naar de dekolonisatieoorlog 1945-1950, werd er ongemakkelijke

kritiek geuit door o.a. Marjolein van Pagee. Bij haar en anderen is een

boosheid te bespeuren die me doet denken aan de Zwarte-Piet discussie. Net

zoals de spijtbetuiging van onze regering voor de slavernij geen waarde heeft

als zij niet ook breed gedragen wordt door de blanke gemeenschap, zo ook is een

spijtbetuiging voor het structurele geweld toegepast in Nederlands-Indië

onvoldoende als de Nederlandse gemeenschap dit onrecht niet erkent. Pas als wij

ons in Nederland beter kunnen vereenzelvigen met het lot van de Indonesiërs

gedurende de periode 1945-1950, zal het dekolonisatie-onderzoek haar noodzaak en

waarde bewezen hebben.