(English summary follows dutch)

Dordrecht

Ramon and

Marie Maddamin in hun huis te Dordrecht, vol herinneringen aan Suriname en

Indonesië.

Tijdens mijn bezoek aan de tentoonstelling "Koloniale oorlog

1945-1949" in het Verzetsmuseum te Amsterdam kwamen twee gedachten steeds bij mij op: allereerst het gevoel

dat ik mij gelukkig mocht prijzen nooit in de positie te zijn geweest van die

Nederlandse soldaten, die jonge opstandelingen moesten doodschieten. Ten

tweede, het besef dat het jarenlang ingeslepen superioriteitsgevoel bij de

koloniale gemeenschap en hun gebrek aan respect voor de inlandse bevolking, de

conditie moet hebben geschapen waarbinnen de begane wreedheden werden toegelaten.

Maar klopt deze voorstelling van zaken wel? Ik bedoel, is dit

het volledige beeld? En zo ja, hoe is dat na te gaan? Hoe werd die koloniale

oorlog door Indonesiërs ervaren? David van Rijbrouck is Bahasa (de taal in

Indonesië) aan het leren om de mensen te kunnen interviewen die deze oorlog nog

hebben meegemaakt "aan de andere kant". Ik moet het helaas proberen in

het nederlands. Daarvoor kon ik Ramon en Marie Maddamin in Dordrecht bezoeken.

Ramon is de oudoom van Ravie Ananda, die ik beschreef in mijn blog

"Kebumen, past and present" maar die zijn website over o.a. de geschiedenis van

Kebumen, alleen in het Bahasa schrijft. Ravie informeerde me over zijn oudoom

die nu in Dordrecht woont, maar in Suriname is geboren en een paar keer Kebumen

heeft bezocht. Wat is zijn geschiedenis?

Groningen,

Suriname

Ramon's moeder Samilah (geboren in Kebumen; ~1902 - 1984) kwam

als jong meisje in 1923 naar Suriname. Ze was mogelijk geronseld, maar was ook

boos op haar echtgenoot, bij wie ze een dochter, Siti Maryam, achterliet.

In Suriname trouwde Samilah met Karis Maddamin (verkeerde

spelling van Amadamin), die een jaar eerder uit Tjilatjap (Java) was gekomen. Ze

ontmoetten elkaar in de plantage "Peperpot". Later vestigden ze zich

in Groningen (even ten westen van Paramaribo) als kleine landbouwers. Ze kregen

7 kinderen, waaronder Paing Radjingun (woont in Groningen, Sur.), Karisah

(21-11-1933 - 3-11-2007), Rohmat (Ramon; woont in Dordrecht) en Joenoes (woont

in Rotterdam).

Toen Ramon 19 was ontvluchtte hij zijn ouderlijk huis en trok

naar Paramaribo. Daar werkte hij een aantal jaren voor de journalist André Kamperveen,

één van de mensen die op 8 december 1982 door Bouterse en de zijnen vermoord

is. Hij heeft verschillende keren zijn familie in Kebumen bezocht.

Links,

Ramon's ouders, Karis Maddamin en Samilah, op latere leeftijd in Groningen,

Suriname (rond 1960). Rechts, Ramon op bezoek in Kebumen bij de ouders van

Ravie in 1985. Rechts onder, Ravie met zijn vrouw en zoontje in 2015.

Kebumen,

Indonesië

In Kebumen trouwde Ramon's halfzuster, Siti Maryam met Supandi.

Zij kregen 6 kinderen. Op 19 december 1948 vluchtte Siti Maryam voor de

Nederlandse patrouilles ("Politionele Actie 2") de bergen in, naar de

desa Binangun. Daar werd in 1950 hun jongste zoon Sumadi geboren. Hij trouwde

met Hanimah en hun kinderen zijn Ravie Ananda en zuster Aila Rezania. Rond 1980

werkte Sumadi op dezelfde copra-fabriek (Mexolie) als mijn vader rond 1934.

Na 1946 kwam Kebumen in het territorium van de Republiek

Indonesia te liggen. Wat gebeurde er tijdens de Koloniale oorlog in Kebumen?

Op een van zijn vele website-hoofdstukken vertelt Ravie Ananda

hoe de Nederlanders op 19 december 1948, tijdens "Dutch Military Agression

II" Kebumen binnentrokken. Zij bezetten snel het terrein van Mexolie, de

copra-fabriek waar mijn vader rond 1933-'35 werkte. Vier mensen ("youth

leaders and employees of the plant") werden gevangen genomen, ondervraagd

en op de tennisbaan tegenover het huis van mijn ouders doodgeschoten. Het huis

was door de Kempetai (Japanse militaire politie) gebruikt als hoofdkwartier en

werd nu door de Nederlanders ingericht als commandopost. Later werd het

overgenomen door het Indonesische leger, zoals ik kon ervaren tijdens mijn

bezoek in 2000.

Op

het Mexolie-terrein: Links, het huis van mijn ouders en de tennisbaan in 1933.

Rechts, het huis als militair hoofdkwartier en dezelfde tennisbaan waar

executies werden verricht.

Koloniaal geweld

In het NIOD-blog "Nederland en de Indonesische

onafhankelijkheidsstrijd" van 13 augustus 2015 staat geschreven:

"In een

nog nauwelijks publiekelijk opgemerkt boek geredigeerd door Bart Luttikhuis en

Dirk Moses, Colonial counterinsurgency

and mass violence (2014), plaatsen achttien Nederlandse en buitenlandse

auteurs het conflict in een koloniale en internationale context. Een bijdrage,

van de Zwitserse historicus Rémy Limpach, vraagt bijzondere aandacht.

Het boek van Luttikhuis en Moses (Routledge, 2014) kost $150.

Gelukkig is het gebaseerd op een speciale uitgave van de Journal of Genocide Research, waarin ook een artikel van deze

auteurs (vol.14, 3-4; pag. 257-276; 2012). Zij schrijven: "Soldiers

entering the violent conflict, including those coming from a background of

armed resistance against the German occupier in the Netherlands, could be

socialized to regard ‘excessive’ violence as normal and acceptable." "Could be socialized", d.w.z. gewend

doen raken aan het geweld.

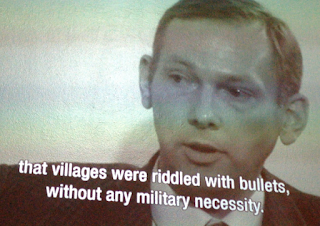

J. Hueting, die in december 1969 hierover geinterviewed werd

door de Volkskrant, geeft er een voorbeeld van. Hij vertelt tijdens een later

bezoek aan dezelfde kampong waar ze toen jonge mannen te pakken hadden gekregen

en langs de weg hadden neergezet: "Ik kan me pijnlijk goed herinneren dat

de chauffeur van de voorste wagen, een Brabantse jongen, uit zijn truck stapt

en zijn lichte mitrailleur meeneemt, een van de Owen guns die we gekregen

hadden in J(?), het hoofdkwartier,.... en zo eens rondkijkt.... en naar zijn

pistool-mitrailleur kijkt....en.....hij ontgrendelde de mitrailleur en schoot 2

gevangenen dood.... om z'n Owen gun te proberen..."

Indonesisch

onderzoek

Ook van Indonesische zijde wordt onderzocht wat er in die Koloniale

oorlog gebeurd is. Zoals hierboven gemeld vertelt Ravie Ananda op zijn in het

Bahasa geschreven website in tientallen verhalen wat er tijdens de Politionele

Acties 1 en 2 en later rond Kebumen gebeurd is.

In een reportage van Max van der Werff (NCRV TV) en de

Indonesische onderzoeker Ady Setyawan, die Ravie Ananda hebben bezocht, wordt

verteld hoe het Nederlandse leger op de weg van Gombong naar Keboemen een

marktplaats bij het dorpje Karanganyar met artillerie beschoten heeft. Volgens

Ravie's verslag ("Herinnering aan de kannonade op Candi-Karanganyar")

vond de artilleriebeschieting plaats op zondag (Wage) 19 oktober 1947, waarbij 786 dorpelingen omkwamen en een

tiental militairen (van het Republikeinse leger, TNI). Het is mij tot nu toe

niet gelukt dit na te gaan in de archieven van de KITLV en NIOD, maar zijn

verhaal vertoont grote overeenkomst met het bloedbad in Rengat op Sumatra op 5

januari 1949 (!), waarover gerapporteerd wordt in de NRC van 13/14 februari

2016. Bij die aanval kwamen meer dan 1000 Sumatranen om het leven.

Datum

beide foto's: 8 augustus 1948. Links, van de website van Ravie Ananda,

"Pancasila, Kebumen2013" (foto uit archief van het KITLV). Ravie's

onderschrift suggereert dat de Nederlanders de terrorist Jatin zullen

executeren. Rechts, Fotocollectie Dienst voor Legercontacten Indonesië. Reportage

/ Serie

[DLC] Evacuatietrein vanuit Gombong. Nummer archiefinventaris:

bekijk

toegang 2.24.04.01. Bestanddeelnummer

3626. Gombong ligt even ten westen van Kebumen.

In een ander verhaal op de website van Ravie Ananda toont hij

een voor mij aangrijpende foto (uit het KITLV archief), met een legenda waarin

hij lijkt te suggereren dat de gevangene Jatin door de Nederlanders

geëxecuteerd zal worden. Maar het

KITLV-bijschrift bij een foto van dezelfde gebeurtenis vertelt een ander

verhaal:

"Een belangrijke bijdrage in het

herstel van orde en veiligheid rond de Status Quolijnen (o.a. bij Gombong),

levert de samenwerking tussen de Nederlanders en de Daerah (districts)politie.

Zij bestaat uit agenten, gerecruteerd uit de kampongs en dessa's, die de patjol

(schop) voor de karabijn hebben verwisseld. De Daerah-politie heeft in de

afgelopen maanden geleerd efficient te werken. Enkele keren konden door deze

politie grote en belangrijke arrestaties worden verricht. Het gelukte de

Daerah-politie van Gombong de hand te leggen op een gevreesd terrorist met

name: Jatin. Het is nog maar een jongen, maar desondanks heeft hij negen

moorden en talloze plunderingen op zijn kerfstok."

Voor het lot van Jatin moet gevreesd worden. Maar door wie zal

hij geëxecuteerd worden, door de Nederlanders of door Daerah-politiemensen? En

wat waren dat voor mensen? Hoe verschilden zij van de KNIL-militairen in het

Andjing Nica Bataljon dat nauw samenwerkte met de Daerah?

Een

ingewikkelde geschiedenis

Na 60 jaar keerde ik voor het eerst weer terug naar Java. Voor

mij was één van de raadsels van Indonesië, van de mensen daar, het ontbreken

van haatdragende gevoelens jegens de Nederlandse toeristen (Dat was op Curaçao

wel anders!). Ook in het filmpje van Max van der Werff wordt dit opgemerkt in

een interview met een oude man.

Tijdens de Koloniale Oorlog (Politionele Acties 1 en 2) kwamen

~6000 Nederlandse soldaten om tegenover ~150,000 Indonesiërs. Dat lijkt een

Israelisch-Palestijnse verhouding. Maar is dat wel zo? Zijn niet veel

Indonesiërs omgekomen tijdens schermutselingen (moordpartijen) tussen eigen

groepen? En als dat zo is, zou deze ingewikkelde geschiedenis de reden kunnen

zijn waarom er geen speciale haat gevoeld lijkt te worden jegens de

Nederlanders?

Een informatief artikel over deze ingewikkelde geschiedenis, ook

wel de bersiaptijd genoemd, is dat

van William H. Frederick (Ohio University) in de Journal of Genocide Research (vol.14, 3-4; pag. 359-380; 2012),

getiteld "The killing of Dutch and Eurasians in Indonesia's national

revolution(1945-49): a 'brief genocide' reconsidered." Op pag. 369 worden

hoge getallen genoemd voor het aantal gedode Nederlanders en Indo's (Euraziaten).

Zie echter het artikel van Bert Immerzeel in Java Post. Of het

"genocide" genoemd moet worden blijft een vraag, maar duidelijk wordt

gemaakt dat het buitensporige "dekolonisatie geweld" een gevolg was

van Nederlands en Japans kolonialisme en van raciale spanningen, niet alleen

tussen Indonesiers en Nederlanders, maar ook tussen etnische Indonesiers en

Indo's.

De

film "Merdeka" gezien in het Verzetsmuseum in Amsterdam: Hoe moeilijk,

ja onmogelijk is het om de geschiedenis te verbeelden?

In de film "Merdeka" (Verzetsmuseum, Amsterdam) worden

mensen als Hatta ("National Hero"; Minangkabauer), Nasoetion ("National

Hero"; Bataker), en Abdulgani (jeugdleider van de PRI; de pemuda, republikeinse jongeren

organisatie) geinterviewed. Ogenschijnlijk zonder haatgevoelens jegens

Nederland vertellen zij hun verhaal en de voor hun gunstige loop van de

geschiedenis na de Japanse capitulatie. De sympathieke indruk die de voor mij

onbekende Ruslan Abdulgani in dit filmpje op mij maakte staat in schril

contrast tot de feiten die Frederick in zijn artikel naar voren brengt over de

PRI en over hen die er leiding aan gaven. De wandaden, begonnen in Surabaya en

voortgezet op het platteland gedurende de bersiaptijd,

waren van een ongekende wreedheid en de verdenking bestaat bij onderzoekers als

Frederick, dat de Republikeinse leidinggevenden en zelfs Sukarno, ervan op de

hoogte waren. Ik ben benieuwd wat Rémy Limpach en David van Rijbrouck hierover

gaan zeggen.

English summary: " Decolonization-2"

Ravie Ananda, who lives in Kebumen and whose father worked at

the same copra-factory Mexolie as my father, sent me photographs of his

great-uncle, Ramon Maddamin. Ramon now lives in Dordrecht, but was born in

Suriname, where he learned to speak Bahasa Indonesia (and Javanese). He visited

the family of Ravie in Kebumen several times. I visited Ramon and his wife

Marie in Dordrecht, where they showed me pictures and a movie about Kebumen.

Ravie has an elaborate website with many historical accounts

about what happened in his town during the colonial war 1945-'49 and later. It

appears that the house where my parents lived in 1933-'35 became a military

headquarter and that the tennis court in front of the house had served as

execution place in 1947.

On Dutch television a documentary has been shown by Max van der

Werff about Ravie Ananda's story of the "Canonade ofCandi-Karanganyar", where hundreds of civilians were killed.

In spite of excesses performed by the Dutch, it was my

impression during my visit to Indonesia in 2000, that the Indonesian people

were not hateful against Dutch tourists. Could the reason for this be that it

were not only the Dutch who committed killings, but also the Indonesians who

committed atrocities against Dutch, Eurasians (Indo's) and their own people,

when suspected not to be loyal towards the Republic? This complex history of

the post-war period, the so-called bersiap,

is described by William H. Frederick (Ohio University) in the Journal of Genocide Research (vol.14,

3-4; pag. 359-380; 2012), entitled "The killing of Dutch and Eurasians in

Indonesia's national revolution(1945-49): a 'brief genocide' reconsidered."